New Ancient Strings

| New Ancient Strings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 22 June 1999 (1999-06-22) | |||

| Recorded | 22 September 1997 | |||

| Studio | Palais des Congrès[a] Bamako, Mali | |||

| Genre | Mande music | |||

| Length | 53:20 | |||

| Label | Hannibal | |||

| Producer | Lucy Durán | |||

| Toumani Diabaté chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Ballaké Sissoko chronology | ||||

| ||||

New Ancient Strings (French: Nouvelles cordes anciennes) is a studio album by the Malian musicians Toumani Diabaté and Ballaké Sissoko, released on 22 June 1999 by the British label Hannibal Records. The album comprises eight instrumental duets composed by Diabaté for kora, a stringed instrument of West African music. Diabaté and Sissoko are esteemed as the best and the second-best kora players of their generation, respectively. Their duets were recorded in a single live take within a marble hallway of Bamako's conference centre on the night of 22 September 1997, coinciding with Mali's Independence Day.

New Ancient Strings was inspired by the 1970 album Ancient Strings, a landmark kora album featuring the musicians' fathers, Sidiki Diabaté and Djelimadi Sissoko. By the mid-1990s, Toumani Diabaté had accrued a significant international profile after recording several crossover collaborations. Having brought the kora to wider attention with these genre fusion projects, New Ancient Strings represented his return to his roots in acoustic Mande music. The music balances elements of traditional and modern styles. Diabaté and Sissoko intended to honour their fathers' musical legacy while showcasing the significant developments that had occurred in Malian music during the nearly three decades since the recording of Ancient Strings. For example, the duo's kora playing makes use of novel techniques not used by their fathers, and also incorporates stylistic flourishes influenced by non-Malian music, such as flamenco guitar.

Although the album's release was not publicized by its label, it received favourable reviews in the Western music press and became popular on "world music" radio stations across Europe and the United States. Its longterm sales have greatly exceeded industry expectations for its genre, as it reached an audience through word of mouth. Widely cited as an exemplary recording of Malian music, New Ancient Strings has become a symbol of the country's musical heritage and the kora in particular. Several artists have cited the album among their personal favourites, notably the Icelandic pop star Björk, who professed its influence on her own music and later recorded with Diabaté.

Background

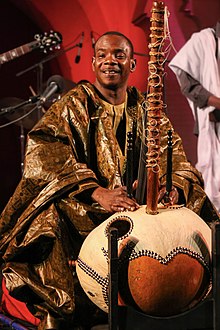

The kora is a 21-string instrument of West African music, similar to the harp or lute, with origins in the 13th-century during the Mali Empire. A kora was historically played only by a jeli (plural jeliw)—also known as a griot[b]—a member of a hereditary class of musicians and storytellers responsible for conveying cultural history through oral tradition.[2] The kora is traditionally played as musical accompaniment for a singer.[3]

Sidiki Diabaté and Djelimadi Sissoko—both kora-playing jeliw born in Gambia from malians parents—relocated to Bamako to join the Ensemble Instrumental National du Mali [fr]. Sidiki's son Toumani Diabaté was born in 1965, while Djelimadi's son Ballaké Sissoko was born in 1967; the two boys, who were also distant cousins, grew up as neighbors. In 1970, the elder Diabaté and Sissoko participated in the recording of Ancient Strings (French: Cordes anciennes), the first album of instrumental kora music.[2]

In 1987, Toumani Diabaté first collaborated with ethnomusicologist Lucy Durán on the production of his debut album, Kaira, which became the first commercially released recording of instrumental music for solo kora.[4] By the mid-1990s, the trend in kora playing, and Malian music in general, moved toward electrification and amplification. Durán—who at that point had produced several more recordings by Diabaté, typically cross-genre fusion projects in collaboration with various other artists—came up with the idea of the "new ancient strings" project. She proposed a "back-to-basics" acoustic recording of kora that would remain faithful to the premise of "ancient strings", while also showcasing how far kora-playing had progressed since the early 1970s.[5] The original plan for the project was a recording of Toumani playing kora duets with his father.[6] However, Sidiki Diabaté died in 1996 before the planned sessions could be realized.

Recording

For the recording of New Ancient Strings, Durán flew from the United Kingdom to Mali's capital city of Bamako with audio engineer Nick Parker.[c] After a period of location-scouting, they received permission to conduct a nighttime session inside the city's then recently completed conference centre, the Palais des Congrès.[a]

Recording took place within a marble hallway between two meeting rooms. As Parker explained in the album's liner notes, the hallway's "hermetic" architectural acoustics were crucial to the recording's natural reverberation. Most other potential indoor recording locations in the country at the time, according to Parker, lacked this quality. Buildings in Mali are commonly constructed with porous materials, usually resulting in subpar resonance; while urban buildings were often made with firmer materials, it was still rare to find one adequately soundproofed to block out the surrounding urban noise pollution. By comparison, Parker felt the Palais des Congrès rivaled European recording studios for its remarkable interior silence, and was "all the more extraordinary when you take into account how very quiet these instruments are in reality."[7]

The album was recorded in a single live take on the night of Mali's national independence day, 22 September 1997.[5] Durán and Parker used four omnidirectional microphones and a portable Nagra four-track recorder.[5] The recording team then returned to London, where Parker mixed the album with Tim Handley.[7] The editing process was minimal. No artificial reverb or other effects were applied to the audio.[5]

Music

Composed by Diabaté, the album's eight duets each reinterpret or adapt a piece from the traditional jeli repertoire.[8] Two of the eight tracks are new versions of pieces from Ancient Strings under different titles.[9] Critics have compared the sound of the kora duets on New Ancient Strings to Western classical music. Francis Dordor of the French music magazine Les Inrockuptibles likened the album's fusion of traditional and modern elements to a collaboration between the 18th-century French classical composer Marin Marais and the 20th-century American minimalist composer Terry Riley.[10] Mark Jenkins of the Washington Post said the kora duets "suggest Bach more than Robert Johnson"—distinguishing New Ancient Strings from Diabaté's next album, Kulanjan, a collaboration with the American musician Taj Mahal intended to emphasize continuities between West African music and blues in the United States.[11]

In terms of resemblance to classical music, Diabaté and Sissoko's duets are similar to their father's performances on Ancient Strings, which Durán said "had a very classical feel, almost like Bach with an African tinge."[5] However, Sissoko noted that their playing incorporated techniques that their fathers had never used, such as muffling strings and other techniques inspired by flamenco guitar.[12] According to critic Simon Broughton, the playing on New Ancient Strings sounds "much more effortless than Ancient Strings".[9]

Release

| Chart (1999) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| CMJ New Music Report – New World | 12 |

| World Music Charts Europe [de; nl] | 1 |

New Ancient Strings was released on compact disc on 22 June 1999 by Hannibal Records, an imprint of Rykodisc.[13] The album arrived without promotion or publicity efforts from the label. According to Durán, "it was a fight to get the record company to support the project; they did not believe that anyone would be interested."[5] Within two weeks, Hannibal released Diabaté's album with Taj Mahal, Kulanjan, which also featured Sissoko and other Malian musicians. Kulanjan was promoted with an international concert tour and a budget-priced compilation of recordings from the two musicians' respective back catalogs.[14]

Despite the lack of promotion, New Ancient Strings sold well, its reputation spreading by word of mouth.[5] Tracks from New Ancient Strings received significant radio airplay on "world music" stations. The album topped the European Broadcasting Union's monthly World Music Charts Europe [de; nl] in May 1999,[15] and it spent nine weeks on the American CMJ New Music Report's "New World" chart, peaking at number 12.[16] On 11 July 2006, Rhino Entertainment and Rykodisc made the album available for digital download for the first time.[17] As of 2011, the album had sold more than 60,000 copies—well above expectations for an album of acoustic music in the "world music" category, which more typically would have been expected to sell no more than about 5,000 copies.[5]

Reception

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic |      [18] [18] |

| Christgau's Consumer Guide |  [19] [19] |

| Edmonton Journal |      [20] [20] |

| The Virgin Encyclopedia of Nineties Music |      [21] [21] |

Early critical response to the album from the European and American press was generally enthusiastic. Writing for The Boston Phoenix, American musicologist Banning Eyre called it the "most definitive statement to date" of the Malian kora tradition, writing that "[n]o kora player has ventured so far out of the old tradition, and none has brought more back. The kora's tapestry of rhythms and melodies have never sounded richer."[22] Francis Dordor at Les Inrockuptibles anticipated that the recording would endure as a musicological document of the kora and the music of the Mandinka people.[10] In a review for British magazine The Wire, Julian Cowley predicted the album "will surely prove to be a defining moment in the history of recorded kora music". Cowley praised the musicians for exploring "the technical potential of the instrument and their own innate musicality", creating a fully "contemporary" sound without resorting to stylistic "hybridisation" (in the sense of crossover music).[23]

At JazzTimes, Josef Woodard wrote that "this album, beautifully played and sensitively realized, confirms our suspicions that the kora is not only one of the most fascinating and inspiring instruments in Africa, but in the world at large."[24] Canadian critic Roger Levesque, who gave the album a five-star rating in Edmonton Journal, said it "offers a wonderful, airy, multi-layered sound as a simultaneous source of melody and pulsing rhythms ... but as often as not the two musicians conjure up a dreamlike atmosphere that serves well for ambient aural backdrops.".[20] The American critic Robert Christgau dissented from the otherwise favorable contemporary consensus, rating the album a "dud" in The Village Voice and his Consumer Guide: Albums of the '90s book.[25] Though Christgau enjoyed Diabaté's work with Taj Mahal on Kulanjan, he dismissed Diabaté and Sissoko's record for sounding "as New Agey as its title, which is, oh my, New Ancient Strings".[26]

Legacy

Since its release, New Ancient Strings has continued to receive acclaim from listeners, critics and musicians. In the long run, its success helped to elevate the prestige of kora music on both an international stage and within Mali.[27] Former Malian president Amadou Toumani Touré (in office from 2002–2012) presented important guests and dignitaries with a miniature kora and a copy of New Ancient Strings as a diplomatic gift. The country's national broadcaster, the Office of Radio and Television of Mali (ORTM), regularly used the song "Cheikhna Demba" as theme music.[28]

The album's success has been credited for launching Sissoko's career on the global stage. While Diabaté had already established a substantial profile outside Mali prior to the album's release, the album brought Sissoko's music to a sizable international audience for the first time.[29] In 2021, British journalist Nigel Williamson said Sissoko was second only to Diabaté in terms of global preeminence among kora players.[30] As of that same year, the two musicians remained neighbors in Bamako.[31]

In 2014, Diabaté and his son, Sidiki Diabaté (named after his grandfather), released Toumani & Sidiki, the third album of kora duets in history after Ancient Strings and New Ancient Strings.[32]

The British magazine Songlines ranked New Ancient Strings at 20th place in its 2003 list of the top 50 "must-have world-music" albums[33] and, in 2021, as the third most-essential recording of kora music.[9] Tom Moon included the album in his 2008 book 1,000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die, writing that Diabaté and Sissoko "engage in fiery jazz-like back-and-forth exchanges" and "sustain an intense conversation throughout, trading solo and accompaniment roles seamlessly, generating spiderwebbed clusters of notes that, despite all the finger wizardry, communicate on a pure spirit level."[34] The Observer's Mark Hudson named it among ten recommended records of African music for the unacquainted listener,[35] while Jon Pareles of The New York Times included it among his ten recommended albums of contemporary Malian music.[3]

Björk cited the album's sound as a major influence on her 2001 album Vespertine, noting that it affected her approach to "mess[ing] up the sound of too angelic instruments" such as the harp.[36] Diabaté later recorded with Björk, playing kora on the track "Hope" from her 2007 album Volta; according to Diabaté, "[s]he listened to New Ancient Strings and decided to include kora in her music."[37] Other musicians who have named the album a personal favorite include Malian singer-songwriter Fatoumata Diawara[38] and Italian pianist-composer Ludovico Einaudi.[39] In November 2020, American musician Donald Glover tweeted a recommendation to listen to the album outside.[40]

Track listing

All music is composed by Toumani Diabaté

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Bi Lambam" (lit. 'Today's Lambam') | 5:00 |

| 2. | "Salaman" (dedicated to Diabaté's patron Salama Sow) | 6:14 |

| 3. | "Kita Kaira" (lit. 'Kita Peace') | 9:03 |

| 4. | "Bafoulabe" (lit. 'The Meeting of Two Rivers') | 6:26 |

| 5. | "Cheikhna Demba" (dedicated to Diabaté's patron Cheikhna Demba) | 4:30 |

| 6. | "Kora Bali" (lit. 'It Never Dies') | 9:07 |

| 7. | "Kadiatou" (dedicated to Diabaté's late sister Kadiatou Diabaté) | 7:49 |

| 8. | "Yamfa" (lit. 'Forgive') | 5:11 |

| Total length: | 53:20 | |

- Source material

Diabaté's compositions on New Ancient Strings interpret or adapt aspects of traditional Malian compositions. The following descriptions of the album's source material are adapted from the original CD liner notes.[8]

- "Bi Lambam" is based on "Lambam", a composition dating to the 13th century; a lambam is the traditional dance of the jeliw (griots).

- "Salaman" is based on "Tita", a love song from western Mali.

- "Kita Kaira" is based on "Kaira", a song popularized in the 1940s by Sidiki Diabaté and previously recorded by Toumani Diabaté on Kaira (1988).

- "Bafoulabe" is based on "Mali Sajio", a song commemorating and mourning the killing of a hippopotamus at Bafoulabé in western Mali, where the rivers Senegal and Bafing meet.

- "Cheikhna Demba" is based on "Bambugu Nce",[41] a traditional composition from central Mali originally dedicated to the 18th-century Bambara king Bambuguchi Diarra in praise of his work to construct an irrigation canal from the Niger River to Ségou.

- "Kora Bali" is based on "Tutu Diarria", a traditional composition originally dedicated to the 18th-century Bambara king Tutu Diarria, specifically drawing on the version recorded by Sidiki Diabaté and Djelimadi Sissoko for Ancient Strings.

- "Kadiatou" is based on "Baninde" (lit. 'To Refuse'), a traditional composition originally dedicated to the 19th-century king Sanuge Gimba, who ruled a town called Kaba near the Mali–Guinea border.

- "Yamfa" is based on the traditional composition "Alla l'aa ke" (previously recorded by Diabaté on Kaira) and a melody composed by Nene Koita, Diabaté's mother.

Personnel

Credits adapted from the original CD packaging and liner notes.[7]

- Toumani Diabaté – kora

- Ballaké Sissoko – kora

- Lucy Durán – production, photography, liner notes

- Nick Parker – recording engineer, editing, mixing, liner notes

- Tim Handley – editing, mixing

- Olivia Design – artwork

Notes

- ^ a b c Completed in 1995, the Palais des Congrès de Bamako was officially renamed the Centre International de Conférence de Bamako (CICB) in 2006.[1]

- ^ While the French term griot is more widely circulated among English speakers, Sissoko has expressed preference for the Bambara word jeli.[2]

- ^ Diabaté, Durán and Parker had previously worked together during the 1987 recording of Kaira.[5]

References

- ^ Diakité 2018.

- ^ a b c Sawa 2021.

- ^ a b Pareles 2006.

- ^ Durán 2011, p. 246.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Durán 2011, p. 247.

- ^ Troughton 2014.

- ^ a b c Durán & Parker 1999.

- ^ a b Durán & Parker 1999, "The tracks".

- ^ a b c Broughton 2021.

- ^ a b Dordor 1998.

- ^ Jenkins 1999.

- ^ Robert 2021.

- ^ Rykodisc 1999.

- ^ Morris 1999, p. 16; Renton n.d..

- ^ World Music Charts Europe 1999.

- ^ Hendrickson 1999, p. 32.

- ^ AllMusic n.d.

- ^ Phares n.d.

- ^ Christgau 2000, p. 78.

- ^ a b Levesque 1999, p. C4.

- ^ Larkin 2000, p. 121.

- ^ Eyre 1999, p. 27.

- ^ Cowley 1999, p. 51.

- ^ Woodard 1999.

- ^ Christgau 1999a; Christgau 2000, p. 78.

- ^ Christgau 1999b, p. 197.

- ^ Durán 2011, pp. 247–248.

- ^ Durán 2011, p. 248.

- ^ Birchmeier n.d.; African Business 2005, p. 66; Durán 2011, p. 249; Williamson 2021.

- ^ Williamson 2021.

- ^ Pajon 2021.

- ^ Durán 2014, p. 32.

- ^ Church 2003, p. 20.

- ^ Moon 2008, p. 221.

- ^ Maal & Hudson 2005.

- ^ Beauvallet 2007.

- ^ Honigmann 2008.

- ^ Quarshie 2020.

- ^ Birrell 2013.

- ^ Kiefer 2020.

- ^ Durán 2013, p. 243.

Sources

- Anon. (n.d.). "Toumani Diabaté / Ballaké Sissoko | New Ancient Strings | (Digital Download - Rhino / Ryko #) | Credits". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- Anon. (1999). "New Releases from Rykodisc/Hannibal/Gramavision". Rykodisc.com. Rykodisc. Archived from the original on 6 January 2000. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- Anon. (May 1999). "Mai 1999". GiftMusic.de (in German). Berlin: World Music Charts Europe [de; nl] & Gift Music GmbH. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- Anon. (June 2005). "Like fathers, like sons: masters of the kora". African Business (310). London: IC Publications Ltd.: 66. Gale A134274614.

- Beauvallet, Jean-Daniel (23 April 2007). "Björk raconte Volta sur lesinrocks.com" [Björk talks Volta with lesinrocks.com]. Les Inrockuptibles (in French). Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- Birchmeier, Jason (n.d.). "Ballaké Sissoko Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- Birrell, Ian; et al. (18 January 2013). "Mali's magical music". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- Broughton, Simon (24 August 2021). "Kora Albums | The Essential 10". Songlines. Archived from the original on 15 March 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- Church, Michael (27 June 2003). "World Music: On top of the world; From Salif Keita (left) to Oum Kalthoum, from Gypsy to fado, Michael Church casts a critical eye over Songlines magazine's list of its 50 must-have world-music albums, as reproduced opposite". London: Independent News & Media. p. 20. Gale A104432199.

- Christgau, Robert (31 August 1999a). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. New York. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- Christgau, Robert (September 1999b). "Salif Keita – Title... Papa Label... Metro Blue / Taj Mahal & Toumani Diabate – Title... Kulanjan Label... Hannibal". Spin. Vol. 15, no. 9. New York: Vibe/Spin Ventures, LLC. p. 197 – via Google Books.

- Christgau, Robert (2000). "Toumani Diabate with Balaka Sissoko: New Ancient Strings (Rykodisc '99)". Christgau's Consumer Guide: Albums of the '90s. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. p. 78. ISBN 0-312-24560-2 – via Google Books.

- Cowley, Julian (May 1999). "Toumani Diabate with Ballake Sissoko – New Ancient Strings – Hannibal HN1428 CD". The Wire. No. 183. London. p. 51. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- Diakité, Oumar (12 February 2018). "Réhabilitation du CICB : Le retard de salaires du personnel dû à la lenteur des créanciers du Centre" [Rehabilitation of the CICB: Delays in payment of staff wages are due to the slowness of the Center's creditors]. LeCombat.fr (in French). Bamako. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- Dordor, Francis (30 November 1998). "New ancient strings". Les Inrockuptibles (in French). Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- Durán, Lucy (August 2011). "Music Production as a Tool of Research, and Impact" (PDF). Ethnomusicology Forum. 20 (2). Taylor & Francis on behalf of the British Forum for Ethnomusicology: 245–253. doi:10.1080/17411912.2011.596653. ISSN 1741-1920. S2CID 53986537. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2022 – via soas.ac.uk.

- Durán, Lucy (2013). "POYI! Bamana jeli music, Mali and the blues" (PDF). Journal of African Cultural Studies. 25 (2). Routledge: 211–246. doi:10.1080/13696815.2013.792725. JSTOR 42005320. S2CID 191563534. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 November 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2022 – via soas.ac.uk.

- Durán, Lucy (June 2014). "Reviving Ancient Strings" (PDF). Songlines (100): 30–34. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- Durán, Lucy; Parker, Nick (22 June 1999). New Ancient Strings / Nouvelles Cordes Anciennes (PDF) (CD liner notes and rear cover). Toumani Diabaté with Ballaké Sissoko. London: Hannibal Records. HNCD 1428. Retrieved 15 May 2022 – via the Internet Archive.

- Eyre, Banning (27 August 1999). "World: Ballake Sissoko, New Ancient Strings (Rykodisc)". Arts. The Boston Phoenix. Vol. 27, no. 35. p. 27. Retrieved 13 May 2022 – via the Internet Archive.

- Honigmann, David (1 February 2008). "'We are the memory'". Financial Times. London: The Financial Times Ltd. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- Jenkins, Mark (15 August 1999). "Africa Fete Brings Lilting Accents to 9:30 Club". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- Kiefer, Halle (6 November 2020). "Finally, Some Donald Tweets You Can Actually Feel Good About". Vulture. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- Hendrickson, Tad, ed. (11 October 1999). "New World". CMJ New Music Report. Great Neck, New York: College Media, Inc. p. 32. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2022 – via Google Books.

- Larkin, Colin, ed. (2000). "Diabaté, Toumani". The Virgin Encyclopedia of Nineties Music. London: Virgin Books. p. 121. ISBN 0-7535-0427-8 – via the Internet Archive.

- Levesque, Roger (17 July 1999). "Dip into African-origin discs for authentic roots reflections". Edmonton Journal. ProQuest 252645574.

- Maal, Baaba; Hudson, Mark (24 April 2005). "How to buy: African music". The Observer. London: Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- Moon, Tom (2008). "New Ancient Strings". 1,000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die: A Listener's Life List (pbk ed.). New York: Workman Publishing Company. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-7611-3963-8 – via Google Books.

- Morris, Chris (3 July 1999). "Hannibal's 'Kulanjan' Unites Bluesman Taj Mahal with Malian Kora Music". Billboard. Vol. 111, no. 27. p. 16. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via Google Books.

- Pajon, Léo (9 April 2021). "Mali: Ballaké Sissoko, the kora's discreet champion". The Africa Report. Paris: Jeune Afrique Media Group. Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- Pareles, Jon (2 April 2006). "Sampling the Sounds of Mali Without Leaving Home". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 September 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- Phares, Heather (n.d.). "New Ancient Strings – Toumani Diabaté, Ballaké Sissoko". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- Quarshie, Adam (29 April 2020). "Heal Your Soul: Fatoumata Diawara's Favourite Music". The Quietus. p. 13. Archived from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- Renton, Jamie (n.d.). "Toumani Diabaté – Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- Robert, Arnaud (24 April 2021). "Ballaké Sissoko, Kora Corps: Le griot malien publie un album de duos où Camille, Feu! Chatterton ou Oxmo Puccino s'invitent dans des joutes inouïes" [Ballaké Sissoko, Kora Corps: The Malian griot publishes an album of duets, wherein Camille, Feu! Chatterton or Oxmo Puccino invite themselves to take part in incredible jousts]. Le Temps (in French). Geneva. p. 26. ProQuest 2517080657.

- Sawa, Dale Berning (7 April 2021). "Ballaké Sissoko: picking up the pieces after US customs broke his kora". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- Troughton, Richie (17 June 2014). "Kora! Kora! Kora! Toumani and Sidiki Diabaté Interviewed". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- Williamson, Nigel (April 2021). "Ballaké Sissoko – Djourou". Uncut. No. 287. London: BandLab Technologies. Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- Woodard, Josef (1 November 1999). "Toumani Diabate/Ballake Sissoko: New Ancient Strings". JazzTimes. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

External links

- Archived official webpage at Rykodisc.com at the Wayback Machine (archived 7 October 1999)

- New Ancient Strings at Discogs (list of releases)

- Liner notes via the Internet Archive